The Systems View

“When we try to pick out anything by itself, we find it hitched to everything else in the Universe.”

– John Muir, naturalist and wilderness advocate

Our world is composed of systems—from ecosystems in nature to organizations and technologies in human society. Learning to see, understand, and think in systems is important because many of the biggest challenges facing our world today are the product of system failures and require a systems view to solve.

What is a system?

As Buckminster Fuller famously observed, a system is greater than the sum of its parts. What makes it greater are the interactions and relationships between those parts. Systems thinking educator Linda Booth Sweeney provides a helpful framework for thinking about this, making a distinction between a “system” —where the whole has properties the parts don’t— and a “heap,” or collection of things which has no higher function.

System or Heap?

Imagine a house. A house is a system, made up of many parts that interact together to provide shelter and other services like electricity and plumbing. But if a tornado hits the house and it’s destroyed, it can no longer serve these functions. All the materials and parts may still be there, but the relationships between those parts have been broken and now lie in a purposeless heap.

Systems take many forms. They can be very large (Earth itself is a system) and very small (e.g. a cell). Systems may be physically tangible (like the house) or abstract, such as a governmental system or computer network. They can also be a combination of both. What makes a system a system is that it is composed of “an interconnected set of elements that [are] coherently organized in a way that achieves something (function or purpose).” (Meadows)

Properties of systems

Systems are diverse but they share properties that can help us identify and understand them. Every system has one or more boundaries and may be separated into components or sub-systems. Every system is also contained within multiple higher level super-systems. These features are found across multiple system types and levels.

For example, a door is a system found in a building at a boundary opening. The function of the door is to allow some things to enter and exit the building while keeping other things from crossing the boundary. A door typically consists of two sub-systems: a closure and a means to control that closure, each of which can take diverse forms. The door might be made of wood with hinges and a latch, for example, or it might be a curtain with a hook to hold it aside.

A door is in turn embedded in higher-level super-systems (a wall, a building, a city, the local habitat). Adjacent systems may exist at any of these system levels and can influence the system of interest and may serve similar functions. Adjacent systems at the level of the door might include windows, which also mediate a boundary. At the level of the building, utility systems connect it to other systems.

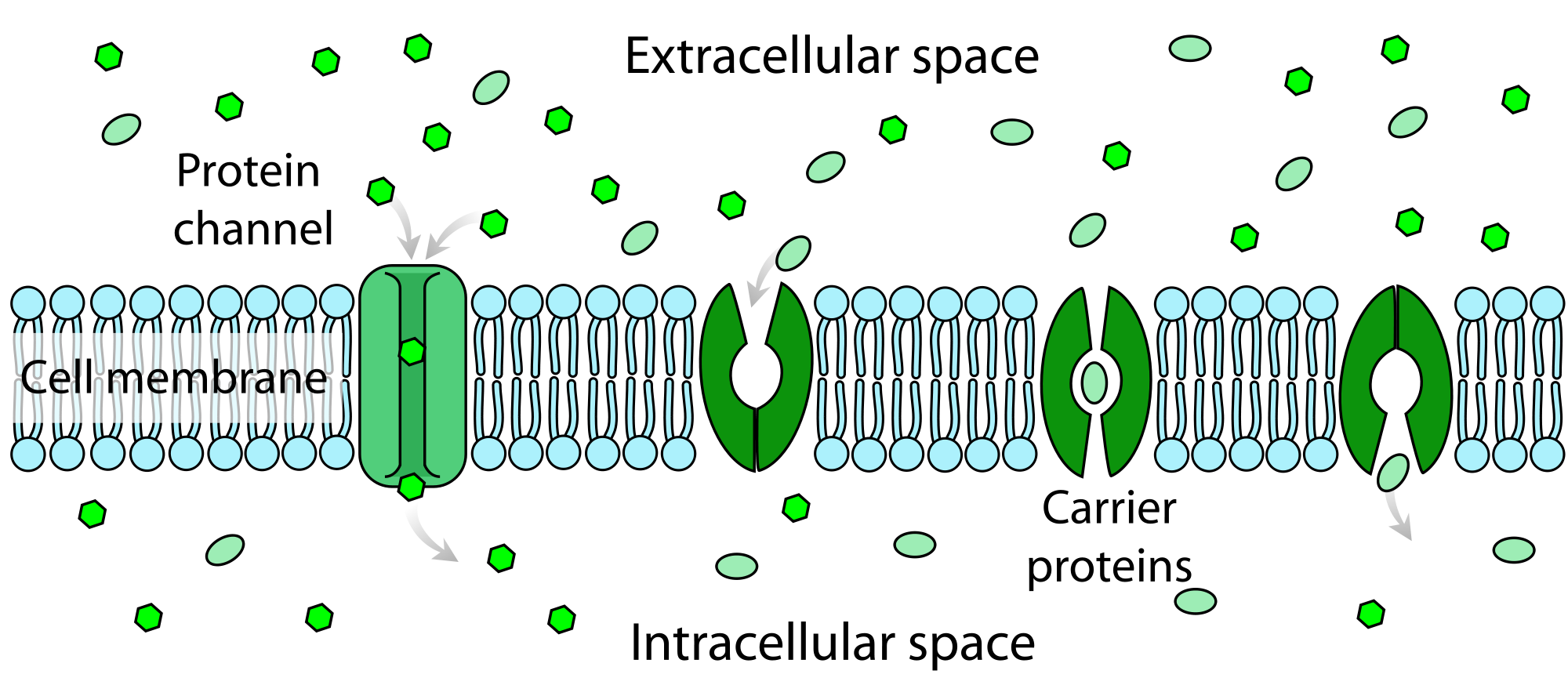

In biology, a transmembrane protein in a cell wall performs a function similar to a door. It allows certain molecules or signals into the cell and passes other molecules and signals out to the external system. The cell in turn may be part of an organ (super-system), that is connected and served by an adjacent circulatory system that knits together many other systems that keep an organism (another super-system) alive.

Everything is connected

Please enable cookies to view this embedded content!

This functionality/content marked as “Google Youtube” uses cookies that you chose to keep disabled. In order to view this content or use this functionality, please enable cookies: click here to open your cookie preferences.

All life is interconnected and interdependent, but we often can’t see how. This video demonstrates that connectivity, showing how whales play a surprising role in reducing carbon dioxide levels in the atmosphere.

One of the key insights gained from a systems view is that everything is connected. No organism can survive completely in isolation from other living things—human beings included. All living things depend on resources and ecosystem services made available through interconnected webs of relationships that compose the living system that is Earth itself. The human-built world is similarly interwoven and complex; no problem or design solution exists in isolation. They are inextricably part of systems of material and energy flows, relationships, and information.

Since the world is full of complex systems, taking a systems view can be a very effective means to understand a design challenge at a deeper level and identify appropriate points for intervention. For a biomimetic designer, being knowledgeable about and aware of system interconnections can help you optimize design outcomes while considering how well your design fits within Earth’s context.

Resources

Thinking In Systems (2008)

This book by systems thinking pioneer Donella Meadows is a wonderful primer on the properties of systems and the factors that govern their behavior over time.

Systems Explorer Worksheet

The Systems Explorer is a tool for diagramming a system. Download this resource for additional information about the tool and how to use it, including a blank version that you can use to diagram your own system(s).

Applying a systems view

Learn more about applying a systems view to your design challenge in the first step of the Biomimicry Design Spiral: Define.

Image Credits

City landscape: public domain Pixabay

House: Eric Allix Rogers CC-BY-NC-SA via Flickr

Tornado damage: Public domain, NOAA

Door: Public domain clipart

Membrane transport diagram: Public domain via Wikimedia

Bibliography

Baldwin, C. Y., & Clark, K. B. (2000). Design Rules, Volume 1, The Power of Modularity. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Farnsworth, M., & MacCowan, R. (2013). Biomimicry Beyond Organisms – Acting and Informing at a Systems-Level. Retrieved from http://www.screendoorconsulting.com/resources/Biomimicry+Beyond+Organisms+for+2013+Biomimicry+Proceedings.pdf

Fuller, R. B. (1975). Synergetics. New York: Macmillan.

Goel, A. (n.d.). DANE. Retrieved from http://dilab.cc.gatech.edu/dane/

Hoagland, M. B., Dodson, B., & Hauck, J. (2001). Exploring the way life works: The science of biology. Sudbury, MA: Jones & Bartlett Learning.

Hoeller, N. (2013). Structure-Behavior-Function and Functional Modeling. Zygote Quarterly Issue 5. http://issuu.com/eggermont/docs/zq_issue_05#

Hawken, P., Lovins, A. B., & Lovins, L. H. (2007). Tunneling Through The Cost Barrier. In Natural capitalism: the next industrial revolution (pp. 111-124). New York: Little Brown and Company.

Maier, M. W. (2009) The Art of Systems Architecting ( 3rd Ed.). Boca Raton: CRC Press.

Mann, D. (2002). Hands On Systematic Innovation. Belgium: Creax.

McHarg, I. L. (1995). Design With Nature. New York: Wiley.

McKeag, T. (2013). Framing Your Problem With The Bio-Design Cube. Zygote Quarterly Issue 6 Retrieved from http://issuu.com/eggermont/docs/zq_issue_06_final/104?e=2346520/3584443

McNamara, C. (2010). Sustainability and Systems Engineering. CSER 2010.

McNamara, C. (2012). System Tools for Interdisciplinary Communication in Biomimicry. Biomimicry Institute Webinar

January 2012. Retrieved from http://biomimicry.net/educating/university-education/webinar/

Meadows, D. (2008). Thinking in Systems. White River, VT: Chelsea Green Publishing

Miller, J. (1978). Living Systems. Bronson, TX: McGraw-Hill.

Open University. (2003). Systems Thinking and Practice: Diagramming. Retrieved from http://systems.open.ac.uk/materials/T552/

d.school, Stanford University. (May 2011). D-School Bootcamp bootleg. Retrieved from http://dschool.stanford.edu/wp-content/uploads/2013/10/METHODCARDS-v3-slim.pdf

Vincent, J. F., Bogatyreva, O. A., Bogatyrev, N. R., Bowyer, A., & Pahl, A. K. (2006). Biomimetics: its practice and theory. Journal of the Royal Society Interface, 3(9), 471-482.

Vogel, S. (2013). Comparative Biomechanics: Life’s physical world. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

White, P., St. Pierre, L., & Belletire, S. (2013). Okala Practitioner. Retrieved from http://www.okala.net/

Wiltgen, B., Vattam, S., Helms, M., Goel, A. K., & Yen, J. (2011, July). Learning Functional Models of Biological Systems for Biologically Inspired Design. In Advanced Learning Technologies (ICALT), 2011 11th IEEE International Conference (pp. 355-357). IEEE.